Woody Rainey teaches at Pratt Institute. He gave a "lecture" recently about his experience at the opening of the Walker Art Center's show about design and the 1960s, Hippie Modernism: the Struggle for Utopia. ONYX was included in the show with examples of our graphics done during the period. Woody attended the opening in October, 2015. The essay below is based on his notes for the encounter at Pratt.

A little less than 50 years ago, I moved to New York from Utah. Within 20 minutes I had a job at I. M. Pei & Partners paying $180 a week. By evening I had a $155 a month rent controlled Studio Apartment. I was thrilled to be in New York and spent most of my time exploring and drawing and discussing ideas with Ron Williams, my friend and classmate from Utah.

We were insider/outsiders in this big town. New York was different then, of course. It was gritty and exciting and affordable. Things were unsettled and everyone seemed to be willing to be poor - exploring ideas, places, personal experiences.

This freedom bred opportunity - the opportunity to be absurd, silly, unreasonable and courageous. Ron and I talked about extreme spaces, about the 4th dimension of form, about society and the environment and geometry and art and Science Fiction. Mostly we talked about architecture and the opportunities to distort and explore space and form in unique ways. When we weren’t talking we were drawing - exploring and illustrating the ideas.

There was Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan and Marshal McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller and Wavy Gravy and listener sponsored WBAI radio. We were aware of Archigram, a London based group of architects who made incredibly beautiful drawings of imaginary architectural conditions. We saw their pamphlets and were somewhat aware of their wild and wide speculations. We liked Ray Johnson and the New York Correspondence School. Johnson, an artist who did “Mail Art,” with a specialized and limited audience. We looked at the San Francisco Rock n Roll poster artists and Tadanori Yokoo.

Everyone was into rock and roll and recreational drugs - and nobody wanted to be the Man. In 1968 we were disappointed by politicians as the “whole world watched” as Chicago police beat up protesters. The war in Vietnam raged and we resisted to our peril. Bobby Kennedy was murdered.

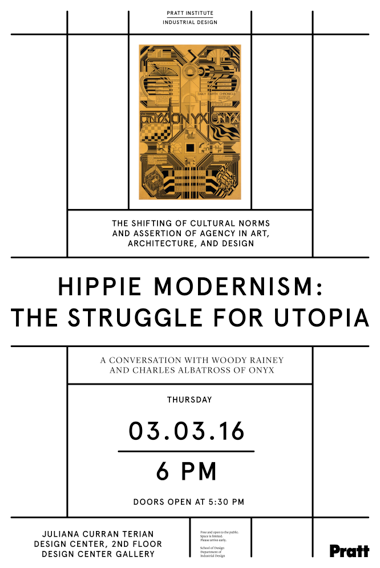

Consequently, our musings were unfettered by decorum. We talked about writing a communal Christmas letter back home, but worried that our audacity wouldn’t be appreciated. Like kids with a clubhouse, we gave ourselves a name: ONYX. ONYX was a beautiful multi-layered stone, representing the richness of thought. ONYX was also mysterious - it could be an acronym for something - we never denied that possibility, though there was never a solution. ONYX looked beautiful graphically. The Logo/Brand/Moniker was in place.

Our Christmas letter became a collage of drawings and poems. Ron drafted the first image and we found ourselves with something unexpected and unique. We showed the Daily Earth Chronicle and the Six foot wide house and the fourth dimension place. We filled in the gaps with amateur poetry. The resulting Broadsheet was like something no one had ever seen. To add to the mystery of ONYX, I became Charles Albatross and Ron became Harvey Grapefruit and Patrick Redson. We protected our real names.

Like cheap apartments and adequate salaries, we could find affordable printers. Bevel Printing and Display gave us 4 or 500 copies for a few hundred dollars. We built a mailing list. We folded and addressed and stamped and mailed the Broadsheets to schools, institutions, publications and people we knew and people we wished we knew, about 200 in all. We included a return address.

The direct response was amazing. We heard from dozens of people...many sending drawings or poems and asking who we were and why were we doing this and who were we doing it for. Ed Ruscha sent his “Twenty Six Gas Stations” book and The Whole Earth Catalog came back from several sources. We discovered other architects and artists who were thinking and doing similar things. We learned about the Ant Farm and SuperStudio and Haus Rucker as they sent their drawings and letters.

We marveled at our discovery and our capacity to connect. We had our forum - our ONYX. If there was an idea now, we could tell the world. For example, I thought I had made a unique discovery: If I stayed up late, it was hard to get up in time for work, so I quit work and slept ‘til noon. Then, I was rested and could stay up even later the next night - awakening mid afternoon the next day. I realized, without the pressure of a daylight/darkness cycle, I could live a 28 hour day - 6 days a week. This unreasonable idea was the source of the next Broadsheet. Why not? Then another happened around the “Reference Point” and musings about the war and Carlos Castanadas. Ron beautifully illustrated some additional ideas about the DEC and original patterns.

The Whole Earth Catalog came to be the focus of a great deal of the communal energy. Later, in a commencement address at Stanford, Steve Jobs called it “Google thirty five years before Google.” Ron corresponded and communicated with them. The community grew and grew through the energy of their poetry. I have saved every issue of the Catalog and their supplements.

Now, this loose network of artists and architects became of interest to journalists and museums. Jim Burns wrote and published “Arthropods”. He opened the narrative with a quote from Antoine de Saint-Exupery:

"What we feel when we feel we are hungry, when we feel that hunger which drew the Spanish soldiers under fire . . . . what draws a man to a poem is that the birth of man is not yet accomplished, that we must take stock of ourselves and the universe. We must send forth pontoons into the night. There are men unaware of this, imagining themselves wise and self regarding because they are indifferent. But everything in the world gives the lie to their indifference."

Burns then explains how he could group the disparate groups into a single genus. A friend told me many years later, it was Burns’ book that convinced him to become an architect. He said it seemed like we were having so much fun and that if he became an architect, he could have fun and perhaps even get laid.

In some subsequent publications, the number of participants grew to include some established names. But now, I was growing restless. The war was raging and Woodstock and then Altamont happens. I created a final Broadsheet based on the dollar bill as Energy Certificate that talks about my planned return to Utah. I go back, but the network works and I am found through my mother. Emilio Ambasz invites ONYX to exhibit at MoMA. But we don’t. I stayed in Utah for a while, got married and built a house. Ron and I go our separate ways. When I return to New York, Harry Cobb tells me he is glad I got over that “ONYX thing” and Richard Meier says we did “nice drawings.” Somehow, in the mid Seventies, the Sixties ended.

Suddenly, several years ago, we learn that the ONYX broadsheets have been collected at Frac Centre in Orleans, the design museum of France. They are all there with our real names. Including the beautiful musings of Mike Hinge. Then, we hear from a Phd candidate in Art History from Princeton who is doing her thesis on ONYX. Finally, two years ago, the Walker Art Center announces its plans for “Hippie Modernism: the Struggle for Utopia.” We are invited.

Andrew Blauvelt, the show’s originator and curator notes in his introduction:

"Hippie Modernism marks the tension between the modern characterized as universal, timeless, rational, and progressive, and its countercultural other, which adopts a more local, timely, emotive and often irreverent, and radical disposition . . . . The hippie modern is not invoked to delineate a style, but rather to denote a historical moment – the creative eruption of the countercultural period that brackets between the Merry Pranksters" cross-country acid trip and the OPEC oil embargo of 1973 . . . ."

In their catalog essay, Agency and Urgency: The Medium and its Message, Larraine Wild and David Karwan write:

"The major cultural impulses that we now associate with the interrelated social revolutions of the mid-to-late '60s—the antiwar, civil rights, and feminist movements, driven by new ideas of personal liberations and communal engagement — were all supported by inventive and homegrown graphic design . . . focused primarily on the urgency of their communication . . . . Content drove the work . . . multiple modes of illustration, collage, and hand-drawing . . . convey the utopian social and/or political goals of the counterculture"

The Walker show is loosely organized around themes stated in Timothy Leary’s famous dictate: “Turn on, Tune in and Drop out.” The first section explores the notion of expanding individual consciousness through drugs or technological or spiritual means. The second section, “tune in” explores the notion of social awareness and collective consciousness and action with particular attention paid to the role of books, magazines, posters and prints: ONYX, Scanlons, The Whole Earth Catalog. The third: “drop out” is addressed through a diverse range of refusals: Drop City, Ant Farm’s Truck Stop Network.

At the show’s opening, hundreds of locals attended the midnight party - many in Hippie dress. Exhibitors were relatively few, as many have passed on or were unable to travel. During an afternoon discussion, one of the Drop City builders protested his bad reputation for buildings that leak when he demurred: “We were not building houses, we were making ART.” The show is as dense as the catalog and will travel to Cranbrook this summer and on to Berkley next winter.

Woody Rainey, March 2016